W2-0014: Palace of QuetzalpapalotlThe Palace of Quetzalpapalotl is without doubt the finest palatial building at Teotihuacan. With its large, painted, tablero-style lintels and ornately carved pillars inlaid with obsidian and mica, there is no doubt that it was designed to stand out as an architectural masterpiece and exude wealth and power when it was completed. The Palace of Quetzalpapalotl is configured around a square courtyard, with four porticoed vestibules leading to rooms on all sides, apart from the eastern side which backs onto the pyramidal temple base that is located in the south-western corner of the Plaza of the Moon. The palace takes its name from the images found upon the pillars which, when discovered in 1962, were thought to be of Quetzalpapalotl – the “feathered-butterfly”.

W2-0016: Close-up of one of the PillarsHowever, research carried out both within Teotihuacan and the cities that it traded with, has identified the repeated use of owl iconography to describe Teotihuacano warriors, priests and its ruling elite. The bas-relief carvings found on the pillars of the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl are now recognised as portraying the Teotihuacano owl, and looking closely at the images on the pillars (fig. W2-0016) the bird-like character is very much in keeping with the owl iconography found all over the city. In fact, the pillars appear to be an assemblage of icons that are found throughout the mural art of Teotihuacan. Starting from the top, the first identifiable icon is the zig-zag band across the top of the pillar, which can be easily identified with the snake-skin pattern seen in the murals of Tepantitla, Tetitla and the Palace of the Jaguars. This icon is particularly clear on the headdress of the Jaguar Mural of Tetitla (see fig. W3-0005) and around the headdress and the collar of the Great Goddess of Tetitla (fig. W3-0004).

W3-0005: Tetitla Mural Beneath the snake band, there are four circular motifs on the pillar that would once have held obsidian decorations (there is one left in situ in the bottom-left of fig. W2-0016 where the icon is repeated). This icon is an eye, arguably the eye of Tlaloc, which is used for the eye of the owl (which still features its obsidian decoration) as well as in the “Sowering Priests” mural of Techinantitla (see fig. W3-0008). The Techinantitlan priest’s headdress also features three obsidian mirrors, which can be found beneath the owl. At the centre of the pillar is the head of an owl, who wears a headdress of green quetzal feathers (which is the same worn throughout the murals of Teotihuacan) and has a distinctive crest of feathers around the upper eye. This crest of feathers is found on the main mural in the Palace of the Jaguars above the eye of a jaguar/puma (fig W2-0019).

W3-0004: Tetitla

W3-0004: Tetitla W2-0019: Jaguar Palace

W2-0019: Jaguar Palace W3-0008: Techinantitla

W3-0008: Techinantitla

The owls head itself is found in the headdress worn by the “Great Goddess” in the mural of Tetitla (see fig. W3-0004) and again in the murals of Tepantitla, where it features in both the headdress of the “Great Goddess” and those of the priests who give her offerings (see fig. W2-0016).

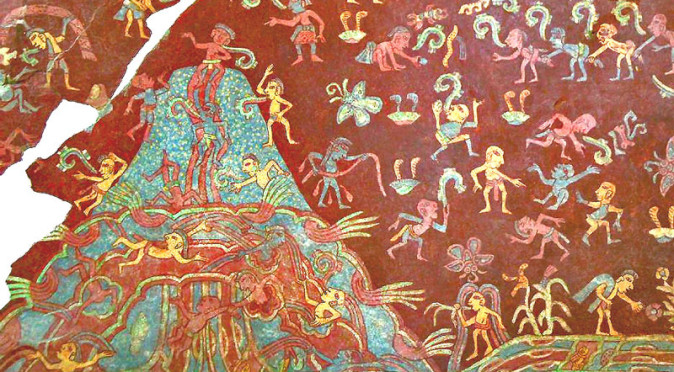

W2-0027: Mural of Tepantitla Also in the mural of Tepantitla, the “Great Goddess” sits on a throne, or possibly wears an apron, that features three obsidian mirrors surrounded by an arc of stars. This imagery is very reminiscent of the three stars we know today as Orion’s Belt, which were highly revered in Mesoamerica, especially by the Maya who believed they represented the Sacred Turtle and the three hearth stones of creation. The same symbolism is found on the pillars of the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl, where the owl appears to sit on a throne inlaid with three obsidian stones (see fig. W2-0016).

The Palace of Quetzalpapalotl was built upon an older structure known as the Temple of the Feathered-Conches, which has been dated to around 200AD. The Temple of the Feathered-Conches was buried beneath the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl in its entirety and archaeologists discovered it still intact. W2-0017: Temple of the Feathered Conches During the reconstruction process, archaeologist designed access to the buried structure and so it is still possible to view it. The pillars of the Temple of the Feathered-Conches are decorated with large carved feathered conches, from which it gets its name. On the base of the temple is a curious row of bird paintings. The birds are certainly not owls and look more like eagles, although they are thought to be green macaws (fig. W2-0017). The birds appear to arch their wing over a number of spearheads and hold an motif that looks like a fleur-de-lis (it could be a speech-bubble rather than a wing).

W2-0017: Temple of the Feathered Conches During the reconstruction process, archaeologist designed access to the buried structure and so it is still possible to view it. The pillars of the Temple of the Feathered-Conches are decorated with large carved feathered conches, from which it gets its name. On the base of the temple is a curious row of bird paintings. The birds are certainly not owls and look more like eagles, although they are thought to be green macaws (fig. W2-0017). The birds appear to arch their wing over a number of spearheads and hold an motif that looks like a fleur-de-lis (it could be a speech-bubble rather than a wing).

2-0016C: Flowering Fruit Icon? The fleur-de-lis icon is very similar to the one used in Mayan art, which is thought to symbolise the ripening of the maize plant with two leaves peeling back to reveal the cob. In the Temple of the Feathered Conches, the logo is either a particularly bad rendition, or is something a little different – perhaps an alternative plant. This icon is found again on the pillars of the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl, where it features where one would expect the bird’s body to be (fig. 2-0016C).

It seems evident then, that the reliefs of the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl are a compilation of murals brought together from around Teotihuacan. This raises the possibility that the reliefs were designed to represent the union between the various compounds of Teotihuacan, including Tepantitla, Tetitla, Techinantitla. These compounds may have been represented by elite familes or religious orders (or both) who controlled individual districts and acted as their religious and political authority, tasked with maintaining law and order. With the construction of the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl burying the Temple of the Feathered Conches, along with its references to green macaws and feathered conches, it is possible that the new palace heralded the beginning of a new era for Teotihuacan – an era of the owl – and the reliefs on the pillars of the palace may have been a new Teotihuacano Royal Standard.

Palace of Quetzalpapalotl Developments within the city, as well as evidence from other cities such as Tikal, Copan, Kaminaljuyu and Monte Alban, between the 4th and 6th centuries does support the idea that a new era was taking place – one that included political and military expansion under the banner of the owl. At Tikal, a Great Lord of the West is recorded as arriving in 374AD and is named as “Owl that Strikes”. Both within the monuments of Tikal and other Mayan cities, this person is depicted as an Owl wielding an atlatl, which has led to the name “Spearthrower Owl”. In 425AD, a new ruler is recorded as arriving from Teotihuacan to take the throne at the Mayan city of Copan. This event was recorded on Altar Q and the new ruler was named as K’inich Yax K’uk Mo, which translates to “Sun-Eyed Green Quetzal Macaw”. Of course, the images of green quetzal macaws that lined the Temple of the Feathered Conches were buried beneath the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl. However, the symbolism was carried forward through the use of green feathers in all the headdresses pictured in the mural-art of Teotihuacan. And so, with the construction of the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl coinciding with a period of Teotihuacano expansionism, and with its iconography matching that found throughout the city and its new empire, it is quite a convincing argument to say that the palace was built as a meeting house for a new political movement or for a new emperor.

I enjoyed the article Robin, however I must inform you that your interpretation of the Fleur de lis symbol is incorrect. In my research I discovered that the ancient symbol that we have come to recognize as the Fleur de lis appears in the art of Mesoamerica at approximately the same time in history as the rise of the ancient Olmecs (1200 B.C. to 400 B.C.). Perhaps not so surprisingly, the emblem of the Fleur de lis in pre-Columbian art and iconography carries the same symbolism of Kingship, as in the Old World, linked to a Trinity of gods, a Tree of Life and a mushroom of immortality. I found that in both hemispheres the Fleur de lis symbol is associated with divine rulership, linked to mythological deities in the guise of a serpent, feline, and bird, associated with a Tree of Life, and a trinity of creator gods. In Mesoamerica, as in the Old World, the royal line of the king was considered to be of divine origin, linked to the Tree of Life. Descendents of the Mesoamerican god-king Quetzalcoatl, and thus all Mesoamerican kings or rulers, were also identified with the trefoil, or Fleur de lis symbol of the resurrected Sun God of Mesoamerican mythology. http://www.mushroomstone.com/fleurdelisorigin.htm

Hi Carl,

Thanks for taking an interest in this article and for taking the time to leave a message. Your article includes an incredible number of examples, many of which clearly show the motif to be a ripened corn with leaves furled back – in particular the Olmec jade figurine (900-300 B.C.), which you describe as a stylised corn. We know that corn/maize was an essential staple and the reason that the civilisations of Mesoamerica became to successful. Unsurprisingly, there are a number of legends that talk of the Maize God being responsible for the creation of mankind. This certainly ties in with your research that shows the motif is also the symbol of kingship and of a divine lineage – in this instance directly descendent from the Maize God. My article doesn’t aim to discuss this in depth and I happily encourage people to visit your site to find out more about the purpose of this symbol.

I am also fascinated by the corpus of images you have collated of mushrooms in Mesoamerican art. In my article on the Cuauhcalli at Malinalco, I proposed that the carved serpent that guards the entrance may have mushrooms pluming from its back rather than spears, as they are commonly believed to be. I would be interested to know your thoughts on this -see http://uncoveredhistory.com/mexico/malinalco/cuauhcalli-malinalco/