Etched into the walls of Building J, the Observatory, are around 40 curious reliefs that date from the period known as Monte Alban II (100BCE-200CE) and feature upside down heads. Bearing in mind the significance of Building J, both in its locale within the city and the practical use that it had, the reliefs must be of monumental importance – quite literally. Many are badly weathered and hard to make out, but there are a few that have been sufficiently sheltered from the elements and cut deep enough to stand out prominently still.

fig. 0255 – Conquest Slab

fig. 0256 – Conquest Slab

fig. 0257 – Conquest Slab

fig. 0258 – Conquest Slab

fig. 0259 – Conquest Slab

The most striking part of the images is the upside-down head. The heads’ position and the lack of iris within the eye (suggesting that that eye is closed) is almost certainly indicating that the subject is dead. The arrangement of the reliefs, which hang like trophies on one of the most important buildings at Monte Alban, has led to the common belief that they record the subjugation of rival tribes and are hence known as the “Conquest Slabs”.

The images are hard to make out, partly due to weathering over the past two millennia, but also because the images are stylised. So in Fig. 0258c you can see a colourised “Conquest Slab”, which is designed to make the imagery more defined. Figure 0258C clearly shows that above the head is the torso with arms outstretched and hands clenched.

Fig. 0258c – Colourised Conquest SlabThe torso has markings/lines across the chest, which could indicate rank or the uniform of a particular tribe – the number of lines is normally 3 or 4. From the lower half of the torso, (the upper half as we look) the legs extend perpendicular to the body, in parallel with the arms, and are bent at the knee so that the lower leg is pointing upward. This position looks unnatural and, even with the relief coloured in, it is hard to visualise what this image is designed to portray. But, if you imagine this to be a man lain on his back on a sacrificial altar, with his head hanging down towards you, his arms outstretched and his legs leading away from you in perspective, then it actually makes perfect sense. We can see this exact position, but in profile, in the Selden Codex (fig. SC1),

The Selden Codex also answers another, more perplexing, mystery and provides a vital clue to what the Conquest Slabs’ message really is. All the images have lines across the face, sometimes horizontally across the eyes and sometimes diagonally across the cheek. First impressions suggest that the lines

Fig. SC1 – Excerpt from the Selden Codexmight be a fabric mask of unknown importance. But, in the Selden Codex we can see the horizontal band across the eyes is face paint and it is present on the sacrificial subject. Face paint was used by warriors, priests and chiefs as an identifier of status and affiliation, and the diagonal make-up is thought to be an identifier of the Zapotec culture1. The horizontal paint across the eyes is thought to indicate the person is a sacrificial subject, but in the Selden Codex (fig. SC1) we can see that both the executioner and the sacrificial subject have black face paint across the eyes. Elsewhere in the Selden Codex the horizontal face paint is used in conjunction with human sacrifice, but not solely to indicate victims, but anyone associated with the act.

City Glyph – TututepecThe final element, above the body, is pictographic and almost certainly represents the name of a place from where he came from or on whose behalf he was sacrificed. In fig. 0258c this looks like a low temple structure on top of a hill, with an “X” and 5 dots along the bottom plus three dots across the middle to indicate the name of this place (I cannot decipher this yet). When looking at the Silden Codex (fig. SC1), we can see that above the body is the heart, which would have been the sacrificial offering, so it would make sense that in the Conquest Slabs it was this place that the person sacrificed. So these images may be entirely symbolic of local Lords sacrificing their cities to Monte Albán and there may have been no physical sacrifice or death at all.

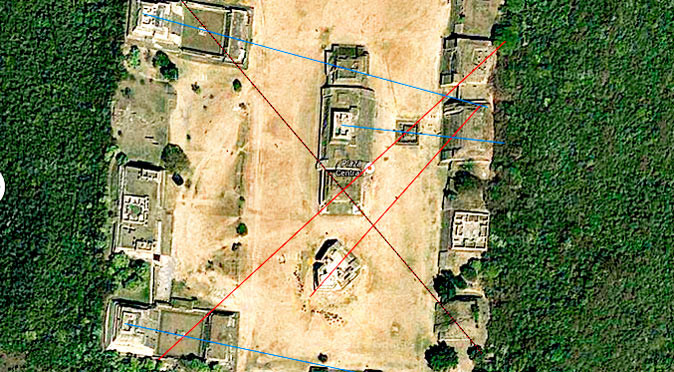

The final piece of the puzzle is why these images are mounted on Building J, the observatory. So in an attempt to pull all the evidence together, I would suggest the “Conquest Slabs” are in fact records of Lords or Priests of the syndicated tribes of the valley who sacrificed their cities for the furtherment of the Zapotec civilisation and Monte Albán. This was most likely part of Monte Albán’s inauguration or during the dedication ceremony of Building J, which seems to have a mysterious and powerful purpose (see the article “Monte Albán – Ancient Observatory).

References:

1 http://mesolore.org/tutorials/learn/14/The-udzavui-Body/150/Painted-Skin