Monte Albán is perched on a hilltop 400m above the valley floor at the epicentre of the Oaxaca Valley. The site was founded in 500BCE, but relatively little was developed during the first two centuries in a period known as Monte Albán Early I. It wasn’t until the next period, known as Monte Albán Late I and dating from 300BCE to 100BCE, that the population grew to more than 5,000 and the city started developing more rapidly. During this time, the Zapotec civilisation, its ideologies and artistic styles all developed formally thanks to the security that Monte Albán provided, acting as its fortified stronghold and capital city, safely looking down on the valley below.

The growth during this period at Monte Albán coincides with a notable decline in the power and population of the nearby community of San Jose Mogote, leading to the suggestion that the population migrated to the new city as part of a planned relocation or following subjugation to the new Zapotec regime. However, more recent discoveries may show that the population at San Jose Mogote actually increased in conjunction with the expansion of Monte Albán during the “Late I” period. During this first period, from 500BCE to 100BCE, the hilltop was artificially flattened and the Main Plaza and Northern Platform were developed. Substructures underneath buildings M and IV were also constructed and the Danzantes were either carved or brought here. Building J, the Observatory, was also built during the preliminary period of development at Monte Albán, either towards the end of the “Late I” or in the early part of “Monte Albán II”.

Monte Albán II is the name given to the period between 100BCE and 200AD. This was the period where Monte Albán grew into the city that would dominate the landscape both physically and politically for the following millennium. The population swelled to 17,000 and the city took shape as the metropolis it can still be seen as today. Through following period known as Monte Albán III, 200AD to 500AD, the city was amongst the most powerful ever seen in Mesoamerica, leaving an enduring mark on pre-Columbian history and securing the Zapotec civilisation its incredible success.

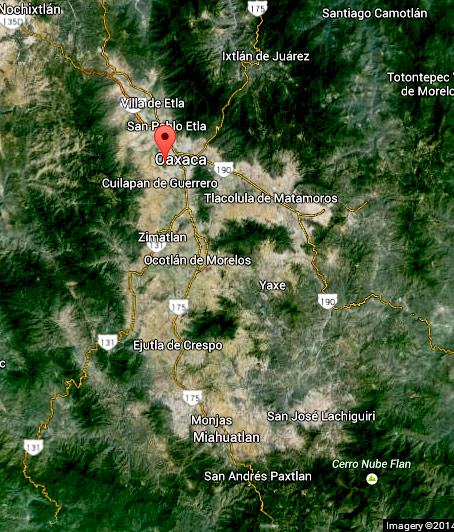

Fig. OVM1 – View of the Oaxaca ValleyMuch of Monte Albán’s success has to be attributed to its location, both within the Oaxaca Valley network and geographically within Mesoamerica at the crossroads between the highlands to the west and the lowlands to the east. The valley is shaped like an upside down “Y” with three arms; the northern section is known as the Etla branch, the eastern section is the Tlocolula branch and southern branch is the Valle Grand. Monte Albán sits at the intersection where the three valleys conjoin in the northern section of the valley (see red marker in fig. OVM1). The three valleys were home to many different tribes prior to 500BCE, but the main centres were at San Jose Mogote in the Etla branch, Yeguih (Yagul) in the Tlalocula branch, and Tilcajete in the Valle Grand. Due to its strategic location, Monte Albán was able to act as a central political centre and unify the communities within the valley and form the Zapotec civilisation. Whether the alliance was by treaty and resulted in the founding of Monte Albán as a unified city, or whether the unification was brought about by force with Monte Albán seizing power thanks to its unassailable hilltop location, is unknown. Many people believe that the hundreds of morbid reliefs found at Monte Albán depicting deformed images of dead people are evidence that it is the latter, though the articles “Are the Danzantes Evidence of an Epidemic?” and “The Conquest Slabs?” may eliminate that theory and reignite the previous belief that the unification of the Valley was a more peaceful affair.

Regardless of how Monte Albán came to power, with its 360° views of the valley it is clear the location enabled Monte Albán to broadcast and assert its power over nearby communities and passing marauders, as well as attracting traders en-route from the Mayan lowlands to the highlands of Teotihuacán. It was the relationship with the latter that was most notable and there is even evidence that a small Zapotec community existed within the city of Teotihuacán. At Monte Albán, there is evidence that the later buildings, such as System IV, were greatly influenced by Teotihuacán architecture and may even have been built to honour visitors from Teotihuacán. Undoubtedly, this relationship greatly assisted the financial strength and political power that Monte Albán held, but ultimately the relationship may have brought about its downfall because shortly after the Teotihuacán civilisation dramatically imploded in c.800AD, the city of Monte Albán lost its pivotal role within the Zapotec kingdom and was largely abandoned.