W0147: View from From South-Western Approach Road From the road approaching La Quemada it is clear to see why historians believed it to be a fortress city, or citadel, for so long. The imposing city is built onto a craggy, insurmountable hill, in the centre of a barren, desolate valley (see fig. W0147). The purpose of such a bold structure set within the remote and inhospitable environment of Mesoamerica’s northern frontier immediately suggests defence and/or trade. This defensive notion is supported by structures on the northern side of the hill where, despite the natural defences offered by cliff edges and the steep gradient of the hill, the occupants of La Quemada still felt it necessary to build a massive defensive wall (see fig. W0170). Regardless of these defences, early researchers noted that the majority of the structures had been subject to intense burning, which suggests the city was attacked and burned down, hence the city was named La Quemada – which translates to “The Burned”.

W170: Northern Walls Taking all the evidence that they had, which included Spanish chronicler Fray Juan de Torquemada’s account that this was a resting place for the Azteca as they emigrated from Aztlán, historians proposed that La Quemada was built in the Early Post Classic Era by the Toltec or Teotihuacano to defend their territories from attacks from and/or to trade with the cultures of the North American south-west. This theory was still being worked through during excavations in the 1960s and many of the structures have been given names based on the idea that La Quemada was a fortress. However, the view of La Quemada as you approach from the south also provides two clear arguments to why La Quemada couldn’t have been designed as a fortress. Firstly, the fortress appearance comes from looking at La Quemada from the south – from the north the site is hidden behind the hill. Secondly, the structure blends almost seamlessly with its environment, making it barely visible even from the south (see fig. W0147). One of the prime objectives of a fortress is for it to be seen and feared.

Regardless of this rather obvious flaw, it was radiocarbon dating that enabled researchers to start looking beyond the walls of the city and into the surrounding lands to find the answers. What they have discovered has only added further mystery, but there is a much better understanding of La Quemada’s physical founding and chronology.

W0174: The Votive Pyramid standing alone on the arid plain (the lake was caused by the damming of the Malpaso River)Far from isolated amongst the desert plains, La Quemada was at the heart of a forested and vegetated area when work began – in fact, the de-forestation occurred during the colonial period, between the 15th to 18th centuries. Evidence found within the Cuartel complex, on the second of La Quemada’s five tiers, shows that work on building the huge platforms had begun in the 4th-5th centuries. Domesticated maize grains were also found within the Cuartel complex, along with evidence of food preparation and cooking, including flaked stone knives, metates, domestic pots, drinking vessels, hearth stones and embers. Farmlands were also discovered outside of the cities walls, where a series of causeways over 170km in length connect over 200 villages, which also featured evidence of agriculture spanning back to the 5th century and beyond. In fact, it is now believed that the barren lands we see today around La Quemada, were lush with agriculture and packed with villages that started to appear from the 1st century onwards.

W0174: The Votive Pyramid standing alone on the arid plain (the lake was caused by the damming of the Malpaso River)Far from isolated amongst the desert plains, La Quemada was at the heart of a forested and vegetated area when work began – in fact, the de-forestation occurred during the colonial period, between the 15th to 18th centuries. Evidence found within the Cuartel complex, on the second of La Quemada’s five tiers, shows that work on building the huge platforms had begun in the 4th-5th centuries. Domesticated maize grains were also found within the Cuartel complex, along with evidence of food preparation and cooking, including flaked stone knives, metates, domestic pots, drinking vessels, hearth stones and embers. Farmlands were also discovered outside of the cities walls, where a series of causeways over 170km in length connect over 200 villages, which also featured evidence of agriculture spanning back to the 5th century and beyond. In fact, it is now believed that the barren lands we see today around La Quemada, were lush with agriculture and packed with villages that started to appear from the 1st century onwards.

W0160: Patio Circular with El Cuartel’s buildings immediately in frontThe Cuartel complex also yielded a considerable amount of information about the reasons for La Quemada’s construction. Working through the rubble, archaeologists discovered that the Cuartel’s buildings once stood three stories high. The lower two stories were constructed in the 6th-7th centuries with the first level thought to be sleeping or resting quarters and the second tier used for food preparation and cooking. The third tier, which was added in the 10th century and was made from adobe, was built as an observatory, looking out the the east. Following this discovery, researchers also found that a room on the lower floor was aligned to be illuminated specifically on the summer solstice. This new understanding of the Cuartel shows that it was integrated with the Patio Circular and a small pyramid which was built as a two metre high facsimile of the massive Votive Pyramid. Surrounding this diminutive pyramid, archaeologists found the disarticulated remains of over 200 humans, including skulls with drill holes and long bones that had clearly been hanging elsewhere at the site and were brought here for rituals. This leads to a new supposition, that the Cuartel was a very sacred space where the religious dignitaries lived and worked by observing celestial activities and making offerings. The discovery that work began on the complexes base in around 300AD also suggests that celestial observation and religion was the purpose for La Quemada construction, whilst the round patio is indicative of a Chalchihuites cultural influence.

W0159: Votive Pyramid, Ballcourt & El Cuartel Through the 7th and 8th centuries, La Quemada expanded with huge buildings and sunken patios being added. In particular, the defining monumental structures known as the Votive Pyramid, the Hall of Columns and the Ball-Court were laid out along a processional avenue, which led from the Votive Pyramid, through the Ball-Court and into the Hall of Columns (see fig. W0159). This building project is clear evidence that La Quemada was growing in power as a religious centre for the surrounding village communities and the Ball Court suggests it was also a political centre as the game was often used to settle disputes. With no clear signs of a ruling elite and an marked absence of ritual burials packed with precious grave goods, it appears the La Quemada was built by the villagers to provide a communal hub. Radiocarbon dating of middens (rubbish dumps) within La Quemada and the surrounding villages, shows that activity within La Quemada and the population of the villages grew rapidly between 600AD – 800AD. Curiously, activity within the city appears to have grown first, suggesting that La Quemada was beginning to drive the surrounding population. This is probably due to the manpower requirement the building project brought, and the need to create a centralised food store to feed them.

Salon de las Columnas – an average man is a little taller than the column stumps found at the entrance The buildings at La Quemada have always been a focus of attention for historians as they are both magnificent and unusual. There is little at La Quemada that conforms with the theories that a remote culture influenced and built the city. The Hall of Columns is a particularly unusual case. Measuring a colossal 42m by 30m, with walls towering over 5m tall and 2.7m thick and filled with 11 gargantuan columns that also measured over 5m in height, which supported wooden beams 13 metres long and a roof 12cm thick, the Hall of Columns would have been the largest roofed structure in Mesoamerica when it was completed in the 8th century. The rows of columns themselves are not unique though, and are in fact another clue that La Quemada and Chalchihuites (also known as Alta Vista) may be linked. At Chalchihuites, a similar Hall of Columns can be found, albeit on a much smaller scale, and it is thought the columns there are aligned to stolstitial and equinoctial events.

W0153: Salon de las Columnas, the midday shadow of southern columns appears to point straight at northern columns

At La Quemada, there is a hint that the columns may also have served this purpose at some point, which would be in keeping with a persistent theme of celestial observation and calendrics encoded within the buildings. Certainly, the odd alignment of the Hall of Columns means that the hypotenuse of the building runs from north to south, and the columns appear to also, rather cleverly, have this alignment (fig. W0153 was taken at approximately midday on the 22nd December 2001, and the shadows of the near columns appear to point to the far columns).

W0157: Votive Pyramid and Stairway The Votive Pyramid is also quite remarkable. Standing at a moderate 12 metres high, it is the unusually steep gradient and non-stepped construction that make it virtually unique amongst the thousands of pyramids and pyramidal temple bases found across Mesoamerica. Built almost as near to vertical as possible, there’s a dysfunctional quality to it with the steps ascending the pyramid being perilously narrow and steep. One doesn’t have to look far to see where the inspiration for this peculiar style came, as the incline and construction method mirrors those used to create the platforms and terraces found throughout La Quemada (in fig. W0157 you can see one such terrace high up to the left of pyramid, which features an identical incline). The Votive Pyramid demonstrates that the construction of La Quemada appears to be independent of any external influence, in particular that of Teotihuacan whose pyramids have a very low gradient and are stepped (they are also tens of times bigger). That said, when looking down from top of the stairs that lead up from the Votive Pyramid (see fig. W0159), the site does have a similarity with Teotihuacan, with a pyramid stationed at the northern end of a processional avenue which terminates with a temple compound on the eastern flank (at Teotihuacan this would be the temple of Quetzalcoatl). These two avenues also share and odd alignment that is several degrees east of north.

Certainly there is a good case for La Quemada to have become a trading ally with Teotihuacan and for ideas and inspiration to have been brought to the area by Teotihuacano merchants. Turquoise, a valuable commodity, was sourced from farther north and could have been handled by La Quemada on its way to Teotihuacan where it could be dispersed along its vast trade network. One would imagine that such a treasured trade would need to be governed by a semi-political centre to prevent the area from becoming destabilised by banditry.  W0164: Perimeter Wall Further ties to Teotihuacan may be evidenced by the defensive walls which were erected in around 900AD. The decline of Teotihuacan in the 8th century is thought to have brought most of Mesoamerica into a state of flux as trade diminished and cities financially failed. During the same period as La Quemada’s walls were erected, Xochicalco was abandoned and many of the Classic Mayan cities were abandoned. However, it is also thought that this universal collapse was caused by a long and catastrophic drought, which firstly triggered a rigorous programme of religious, often human, sacrifice (which at least depleted the food requirement). This type of activity may be witnessed at La Quemada, where the bones of 200 people were buried within the Conjunto Pirámide-Osario complex, and also in a new area erected in the 8th century at the very top of the hill, known as La Cuidadela, where a human was interred upon a small stepped pyramid. Eventually, it is thought that the continued drought across Mesoamerica led people to overthrow their failing divine rulers and abandon their failed cities and religion. Whilst La Quemada does not appear to have had a divine ruler, or indeed any ruler, the site was abandoned shortly after the defensive walls were added, suggesting that the area had destabilised and that the city’s wealth and food stores needed defending.

W0164: Perimeter Wall Further ties to Teotihuacan may be evidenced by the defensive walls which were erected in around 900AD. The decline of Teotihuacan in the 8th century is thought to have brought most of Mesoamerica into a state of flux as trade diminished and cities financially failed. During the same period as La Quemada’s walls were erected, Xochicalco was abandoned and many of the Classic Mayan cities were abandoned. However, it is also thought that this universal collapse was caused by a long and catastrophic drought, which firstly triggered a rigorous programme of religious, often human, sacrifice (which at least depleted the food requirement). This type of activity may be witnessed at La Quemada, where the bones of 200 people were buried within the Conjunto Pirámide-Osario complex, and also in a new area erected in the 8th century at the very top of the hill, known as La Cuidadela, where a human was interred upon a small stepped pyramid. Eventually, it is thought that the continued drought across Mesoamerica led people to overthrow their failing divine rulers and abandon their failed cities and religion. Whilst La Quemada does not appear to have had a divine ruler, or indeed any ruler, the site was abandoned shortly after the defensive walls were added, suggesting that the area had destabilised and that the city’s wealth and food stores needed defending.

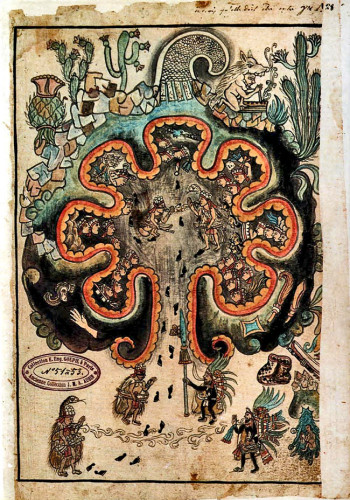

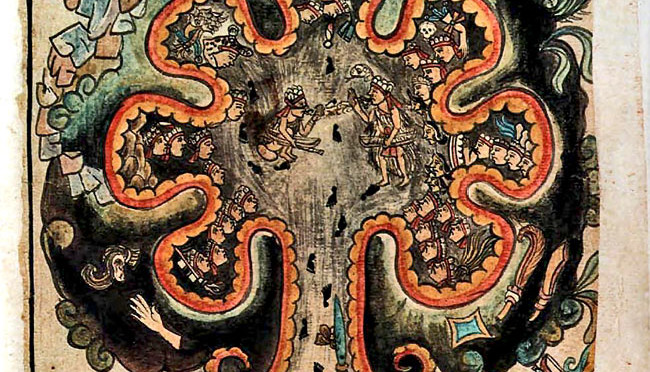

Ironically, the abandonment of La Quemada occurred around the time that historians had originally believed the city to have been built. However, this date does support one early theory made in 1780 by Francisco Javier Clavijero, who believed that La Quemada could be Chicomoztoc, the legendary birthplace of Central Mexican culture. His theory was probably based on the 16th century work of Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl who, in his book “Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca”, drew Chicomoztoc underneath a crooked mountain amongst a desert plain – very similar to that seen at La Quemada

W0149C: Diagram from the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca(see figs. W0149C (below) and W0170 & W0149 at the top of this article). According to Aztec legend, Seven Tribes lived within Chicomostoc, which was a cave-dwelling in a land known as Aztlan. The “Seven Tribes” gradually left the cave to venture south in search of new lands. The Aztec, or Mexica as they were known, were the last to leave and noted the event on their calender as Year 1, which equates to 24th May, 1024AD. Unfortunately, there isn’t a cave network beneath La Quemada, which seemed to leave this idea redundant. However, the cave could be metaphor for a womb and the gradual exodus symbolic of the births of seven tribal leaders – either as septuplets or simply having a shared lineage. The diagram produced by Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl, a direct descendent of the Mexica royal lineage, does portray the cave in a very womb-like way, with a father figure with a serpent headdress entering the womb (determined by the footprints leading in) and instructing the foetal warrior who has just emerged from the eagle cave (fig. W0149C ). If the cave is metaphorical, then La Quemada does make the ideal birthplace for the “Seven Tribes”, with seven Great Rulers being born at La Quemada and then making their homes amongst the villages of the Malpaso Valley, a region they named Aztlan. Then, possibly following a continued drought, they steadily fled south and resettled – starting in the 10th century and finishing in 1024AD with the departure of the final tribe, the Mexica. This is certainly a possibility, and curiously excavations in 2012 uncovered a number of pots painted with motifs of an eagle with a serpent in its beak. This is thought to relate to a Huichol myth where the eagle eats clouds (represented by the serpent) to prevent flooding, but it was also the prophesied vision that led the Mexica to settle and build Tenochtitlan – an event that is commemorated on the Mexico flag today.

Following the abandonment of La Quemada, the site was still used sporadically – either by pilgrims, or by the occasional nomadic tribe that stumbled across it before moving on.

The image references seem to be a bit off on this page–you have W0159 three times when it should presumably be W0153 and W0157 at least once each?

Again, love the site!

Hi Oliver,

Thanks for pointing that out. I have corrected the errors and greatly appreciate your positive comments.

Cheers, Robin

The name Chicomostoc has long been translated as meaning seven caves. In the 2009 Dumbarton Oaks publication by Dana Leibersohn the word Chicomostoc is also translated as meaning seven barrancas. As the mountains to the west of these ruins in notable for the many very deep barrancas it reasonable to assume that Chicomostoc is a name that applies to that mountainous area as well as these ruins. It has long been noted that there was some kind of travel and trade through those very mountains from the coastal areas to the area of these ruins. The peoples of those mountains are now known as Huichol (Wuixarika), Cora, Tepehuan, Tepecano, and Mexicano (Aztec). All members of the group making up the former Aztatlan state

Hi Dave, thanks for sharing your knowledge. It is a mysterious and evocative place that certainly feels fitting for the Chicomostoc legend. Thanks again for contributing. All the best, Robin