The history of Chicanna spanned a millennium with its origins in the Preclassic and its demise in the Post Classic. Although very little research has taken place, it is possible to piece together the history of Chicanna from the extant buildings and archaeological evidence that was exposed during their preservation. This is because the builders used distinctive architectural styles that are synonymous with the late Classic Era. They also feature carved facades that contain detailed information about the evolving religious and political practices of the Maya.

Early History of Chicanna

The key to understanding the early history of Chicanna is its location in the densely populated Rio Bec region. To date, more than 45 ancient Mayan settlements and cities have been discovered in the area. Undoubtedly, the River Bec (Rio Bec) was the source of this popularity. Rivers in the Mayan Lowlands are incredibly scarce and the Rio Bec offered a rare permanent supply of food and water.

The region’s early settlers are easily identified. To the south of Chicanna lie the cities of Nakbe, El Mirador, Tikal, San Bartolo and Calakmul. These settlements transformed the social landscape from around 750BC and reached their Preclassic zenith in around 300BC. This Preclassic peak coincides with the first signs of settlement at Chicanna. Migration northwards was motivated by the need to expand territories and develop trade routes. Less fortunate migrants may have been fleeing from the power struggle within the southern region.

Early Development of Chicanna

The first major building to be erected at Chicanna was Structure XI. The central section that runs north to south was the first section to be completed. Built upon a low platform with three entrances facing east, the design is near identical to Chicanna’s other structures. Yet there is strong evidence that it is much older.

The first indication that Structure XI is much older comes from its rough construction. The walls are built from small stone bricks and do not feature any carved decoration. The Classic era buildings are built with large well dressed stone blocks and are covered in carvings. Further evidence of its antiquity is found in the roof vaults. These are of a type unknown to the Classic period, which suggests that they were built in the Preclassic Era.

A Thriving Community

The internal layout of Structure XI also strikes discord from Chicanna’s Classic era buildings. The central entrance (Room 3) leads into a spacious reception room with a large platform (Room 4). This is reminiscent of the throne rooms pictured in Mayan art. A slender gap in the wall from Room 6 appears to be a service entrance and the opposing wall has an even smaller entrance to private chamber (Room 2). This chamber is only accessible from Room 4 and appears to be a dressing room or place of privacy.

This internal configuration of Structure XI is very functional and would have worked well as a palace for a civic leader or ruler to hold court. In contrast, Chicanna’s Classic era buildings were segmented into individual chambers or dual chambers for ritual purposes. Therefore Structure XI possibly marks the point in the history of Chicanna when it was a simple community (read the article on Structure XI for more information).

Early Classic History of Chicanna

Following the construction of Structure XI, the history of Chicanna falls silent for several centuries. This is a familiar story throughout the Mayan regions and it seems as though the Preclassic Mayan civilisation collapsed between 100AD and 250AD. Although they continued to inhabit their cities and settlements, there was very little development or construction. This period appears to have been brought to a close by the arrival of the Teotihuacano from the far north-west. By 300AD, Teotihaucan was home to 100,000 people and had the wealth and manpower to take control of Mesoamerica.

The extent of Teotihuacan’s influence over Mesoamerica has only recently been revealed. It is now understood that the Teotihuacano took control of key cities across Mesoamerica using trade, marriages and sponsorship. Their integration was so subtle that it’s typically only evidenced by artwork, pottery and chippings of rare green obsidian. However, corroborative texts found at Tikal and Copan have revealed a much richer understanding of their influence. The texts talk of a Lord of the West who appointed rulers in these two locations shortly after his arrival in 426AD (see the history of Tikal for further information). Although there is no such link between Chicanna and Teotihuacan, evidence of trade with Teotihuacan has been found at nearby Becan during the era when both Becan and Chicanna were rapidly expanding.

Middle Classic History of Chicanna

In around 500AD construction work at Chicanna began again with Structure XX. Although finished in the Chenes style, Structure XX is very different to Chicanna’s other buildings. In fact, it appears to be a traditional pyramidal temple with four Chenes range style buildings added around its base. Two lintels in the upper chambers have been carbon dated to 529AD and 683AD. The mismatching dates may be evidence that a 6th century pyramid temple was buried beneath a 7th century rebuild. The lintel from the 6th century temple would then have been reused alongside a new 7th century lintel in the temple.

The Maya are renowned for burying older structures. This custom stems from the ritual of burying rulers and elders within pyramids. These burials placed them directly into the sacred mountain where the underworld was located. The temple on top then acted as a portal to allow the living to communicate with them. These temples were then ritually buried beneath later temples with additional elders or rulers buried within them. This act was symbolic of the cycle of death and rebirth with one temple buried and a greater temple reborn. The additional burials also increased the spiritual power of the building.

Other Middle Classic Structures

Structure III includes Chicanna’s only functional pyramid. The pyramid is positioned to the west of a complex of rooms and dates to around 600AD. This date is midway between the earlier and later dates of Structure XX and it is conceivable that Structure III and Structure XX were very similar until the latter was redeveloped. Like Structure XX, Structure III was also redeveloped later in the history of Chicanna. In fact, rooms were still being added as late as 1040AD. As with Structure XX, the desire to redevelop may have stemmed from an important burial within the pyramid.

Late Classic History of Chicanna

The Late Classic era was by far the most prolific period in the history of Chicanna. Structures I, II, VI, and X were all built between 650AD and 900AD and Structure XX appears to have been rebuilt during this period too. It is easy to identify these buildings from their decorative facades and architecture, which are hallmarks of the Chenes and Rio Bec styles. However, the design of each building is very different and they each appear to have been built to fulfil a specific function. Even the near identical carved artistry has idiosyncrasies that appear to describe each building’s unique function within Chicanna,

A Shrine to the Gods of Time

From top to bottom, Structure XX appears to represent the sacred world of the Maya. The upper chambers face the cardinal points and were probably dedicated to the sun. The high relief masks on the upper tier represent the four Chacs who support the four corners of the sky. The Monster Mouth entrance of the upper southern chamber represents the sacred cave and portal to the underworld. Down below, the central southern chamber was the exit into the underworld. The nine external lower chambers (excluding the southern central portal) were the houses of the Nine Lords of the Night. These lords reigned over the nine full-moons of the Ritual Calendar (see article on Chicanna Structure XX for further information).

A New World Order

The symbolism of Structure XX suggests that it was built to give offerings to the gods that presided over both daily and annual cycles. In particular, the upper chambers appear to have been used to give offerings to the sun and the lower chambers used to give offerings to the moon. Dedicating buildings to the gods was common in the Classic Era because the fate of man no longer lay with powerful rulers. Instead, rulers played the role of divine mediators. Only through their personal sacrifice and observation of religious rituals could the ruler satisfy the gods and bring wellbeing to their citizens. To ensure their offerings were received by the gods, they needed buildings that would beckon them. These buildings were designed to capture the celestial event(s) that the god was associated with as a way of ensuring the god could be seen collecting the offerings.

A Temple to the Setting Sun

With its two mock pyramid towers, Structure I is thought to model the towering pyramids of Tikal’s Great Plaza. This design is typical of the Rio Bec style and it is found throughout the region. However, rather than mimicking Tikal it is likely the twin towers were aligned to two celestial events. The building faces east and has a viewing platform in front of it. This would have made it possible to watch the sun set directly behind the towers or through the ornamental temples that once stood on top. Known as hierophanies, these solar effects would have been considered as visitations.

The most popular alignments for the Lowland Maya were to mark the sunsets on 25th April and 18th August. These dates signified the time to plant maize and the time to expect the first harvest. The hierophanies therefore had a practical application alongside a spiritual one.

The evolution of symbolic architecture

Both Structure XX and Structure I are part of an architectural evolution that combined deeper religious ideas and better technical ability. Previously, religious buildings were mountains of stone with cave-like temples on top. This achieved the symbolism of the sacred mountain and the elevation to observe celestial events on the horizon. Both Structure I and Structure XX still physically resemble the sacred mountain, but they utilise the grandeur of artistry and architecture rather than height and mass. With precision engineering, observation could now be achieved using the markers on the building instead of the horizon. Sighting holes, zenith tubes, shadows and roof combs are just some of the techniques the Late Classic Maya used to observe celestial movements. Meanwhile, the carved artistry on of their facades told a much richer story of their purpose.

Architecture of a Mature Community

Architecturally, Structure II is the logical outcome of Chicanna’s architectural evolution. Structure II is as impressive Structure XX and Structure I, but required much less stone. Architectural finesse had now replaced hard labour and moving hundreds of tons of stone through the jungle was no longer required.

Perhaps most importantly, the imagery of Structure II was carved into its brickwork. This meant it required only a thin layer of stucco (a primitive plaster made by burning limestone). A large number of trees were required to make only a small amount of stucco and in the damp lowland jungles the stucco did not last very long. The compact design and carved stonework of Structure II was easy to maintain, broadcast complex religious meaning and was very robust. As such, Structure II is a pragmatic and intelligent solution for a community with limited resources. That it is still standing today is proof of it success.

Post Classic History of Chicanna

While the majority of Maya towns and cities were abandoned towards the end of the first millennium, archaeological evidence shows that Chicanna was still being developed in the eleventh century. Chicanna’s neighbour Becan was also inhabited beyond the collapse of the Classic Era and shows evidence of occupation well into the twelfth century. In fact, the Great Classic Maya Collapse seems to have gradually moved north, with the cities of the Southern Lowlands falling first and those of the Northern Lowlands falling last.

Once again, it appears that people abandoned the Classic Maya cities of the southern lowlands and migrated north to the Rio Bec region. This time, their arrival slowly overwhelmed the Central Lowlands and triggered further migration outwards towards the coastal regions. By the thirteenth century, the Post-Classic Maya were forming pockets of isolated territories with fortified cities along the Caribbean coast. The religious fanaticism of the Classic Era was abandoned along with hundreds of cities, towns and settlements in the heart of the lowland jungles. Chicanna would soon be reclaimed by the jungle, a forgotten settlement of a lost civilisation.

Modern History of Chicanna

The modern history of Chicanna began in 1966 when an archaeologist named Jack W. Eaton discovered the ruins during a reconnaissance survey around the outskirts of Becan. The site was then rediscovered in December 1967, when R.S. Callvert, Robert Snethen and Francis Murphy stumbled across it whilst trying to relocate a large twin-towered building designated as “Rio Bec B”. Research formally began at the site in 1970 with the excavation and consolidation of Structure II and Structure XI. It wasn’t until the 1980s that Structures I, II, III, VI and XX were excavated by INAH under the direction of Ramon Currasco and Roman Pina Chan.

While the surrounding area has not yet been excavated or understood, it is fairly certain that all the major buildings have been revealed.

Proposals on the Purpose of Chicanna

It is not often necessary to propose the purpose of a settlement, town or city, as their purpose is typically to house and organise a community. The early history of Chicanna traces exactly this kind of development with a small settlement growing into a structured community. However, the Late Classic history of Chicanna is not so easy to understand. Firstly, how can a small community maintain independence in the shadows of a large city like Becan? Secondly, how does a small community attain the skill and manpower to build structures that are architecturally and artistically as good as many cities accomplished? Lastly, what need would a small community have for such a number of exquisite buildings? There are many viable proposals to answer these questions.

A Political Outpost?

Cites often installed a political elite into nearby communities to assimilate them into their political jurisdiction. They then built municipal buildings to assert their power over the population. The buildings of Chicanna are powerful municipal buildings and could arguably have been built for this reason. However, Chicanna was so close to Becan, that it would have been easily controlled from the city. The proximity to Becan would have also deterred any other cities from trying to establish political control of Chicanna.

An Elite Suburb?

Whilst the close proximity of Chicanna to the huge city of Becan defeats the theory of it being a political enclave, it strongly supports the idea of it being a suburb. If this was the case, then the grandeur of its buildings would suggest it was a community of Becan’s elite. Yet there are also problems with this theory. Firstly, Chicanna has no walled defences and would have sat on the very outskirts of Becan, whereas Royal and elite families would typically live securely at the heart of the city. Secondly, there is strong evidence that the Maya only used permanent stone structures for religious and municipal purposes. So if Chicanna was a suburb, then it was one that had its own municipal and religious centre. This suggests that Chicanna had some form of independence from the city, rather than being home to its prestigious leaders.

Independent Cheifdom?

The early history of Chicanna suggests that it developed as an independent settlement. It is possible that it remained the seat of a noble family. As Becan stretched out, Chicanna would have been absorbed politically, with the lord of Chicanna paying tribute to the king of Becan. This would explain why Chicanna had its own religious and municipal buildings, however it doesn’t explain how it had the riches or necessity to build such magnificent buildings.

A Religious Complex?

From the opening chapter in the history of Chicanna, there is evidence that the settlement was founded on religion. Chicanna stands upon a small hill with rocky outcrops. For the Late Classic era builders, this was a hindrance that they had to work around. This is impracticality is further evidence that Chicanna wasn’t built as an elitist suburb, for they would have chosen flat ground for that. Instead, it suggest the location was chosen on its spiritual merits during the Preclassic Era, when constructing stone temples wasn’t a consideration.

Throughout the history and geography of Mesoamerica, hilltop locations were selected for religious reasons. For the Maya, hills and mountains were believed to be incarnate with supernatural powers. They were spiritual places and access-points to the underworld. However, they also provided the elevation needed for celestial observation. It was through celestial observation that priests knew when to perform the various rituals that were required.

Religious Buildings & Complexes

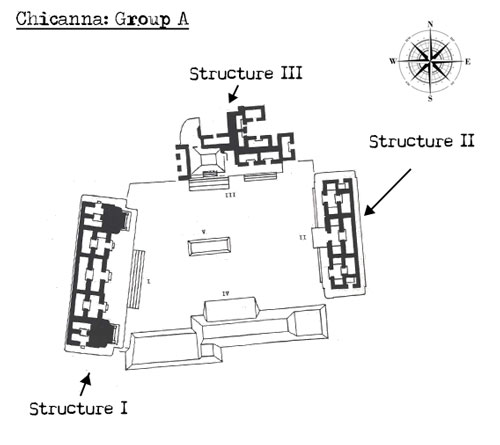

The cluster of buildings known as Group A exhibit all the hallmarks of religious activity. With its twin towers providing markers for the setting sun, Structure I combines symbolic artistry with observational functionality (see the article on Structure I). Structure II faces west and features a monstrous portal to the underworld (see the article on Structure II). These two buildings face each other with the pyramid of Structure III to the north. The three main chambers combine to complete a triadic arrangement. To the Maya, this arrangement symbolised the three hearth stones of creation and gave the group an additional spiritual purpose. A long platform completes the southern edge of the group to create an enclosed religious space and provide a viewing area.

With its mock mountain and monster mouth portals, Structure XX was also clearly built for religious activity. It is also aligned for celestial observation and its upper chambers appear to have been used to give offerings to the sun. Most importantly, it appears to symbolically represent the Mayan universe and probably played a major part in observing the rituals of the solar year (see the article on Structure XX).

The Power of Religion

Mayan life was centred on the observation of time and the performance of religious rituals. These were primarily fixated on the agricultural cycle of maize that the Maya relied on so heavily. Having mastered their agricultural calendar, the Maya moved on to recording other fortunes and misfortunes against cyclical celestial events. The Maya concluded that their own lives were controlled in the same way as the crops. Therefore success could be largely guaranteed if a task was undertaken on the correct day and with an appropriate sacrifice to the governing god. As a result, rulers, heirs, governors, generals and politicians all relied on accurate prophecies to make important decisions. War, marriage, accession ceremonies and funerals were all timed around tables of omens and observations.

The importance of religion helps to explain why the community of Chicanna required such majestic buildings. These structures effectively guaranteed the success of the community. This again suggests that Chicanna was independent and therefore not protected by Becan’s own rituals, which it would have held in its vastly superior religious complex. With this in mind, the theory that it was the seat of a noble family that was subservient to Becan is probably the best explanation for the role of Chicanna.

There is one other attractive possibility. It is possible that Chicanna was a spiritual centre for a small community. As Becan grew, it was commandeered and transformed into an auxiliary religious centre to the city’s own. It may then have functioned as a school or monastery where young royals and priests were trained and practised in the arts and sciences of religious observation.

I visited this site and others in the area about 30 years ago. I had no information on these sited, but now I can learn more about them

Thank you so much for filling in the blanks for me.

Hi Mike,

Thanks for taking the time to leave your comment! I’m really pleased to have been able to help. I will eventually get around to adding those other sites – so do come back!

Thanks, Robin