Chicanna Structure II is without doubt one of the most striking Mayan temples ever uncovered. Built in the early Chintok ceramic phase, Structure II has been accurately dated between 750AD and 770AD. With its ornate Monster Mouth façade, Chicanna Structure II is certainly a striking example of the sophistication and artistic flair of the Late Classic Maya. Each of the teeth, fangs, spiralling plant forms and embellishments were carved upon individual blocks that were then slotted together to create the ornate mosaic that still stands today. Upon completion, the monstrous brickwork jigsaw was plastered with stucco, engraved in fine detail and garishly painted blood red (a patch of this paint can still be seen today in the top right corner of the mouth). Despite being buried and torn apart by the ravaging jungle over many centuries, the jigsaw-like method of construction made it possible to accurately piece the facade back together. Today, Chicanna Structure II stands as it did over a millennia ago and is one of only a handful of Mayan Monster Mouth Temples that can be fully appreciated today.

Symbolism and Meaning of the Chicanna Monster Mouth Temple

Chicanna Structure II was built in a transitional form of the Rio Bec style (the mock-pyramids of the fully developed Rio Bec style were an elaboration of this style, which then transitioned into the Chenes style). The Rio Bec, Chenes and Puuc styles found throughout the region utilised artistic symbolism to represent the sacred cave (this is discussed at length in the article Chicanna Structure I & the Rio Bec Style). The sacred cave was a portal between the middle world and the underworld that enabled communication between the living and the spiritual. Perhaps inspired by watching snakes and crocodiles consume living prey whole, the Maya used the image of a reptilian monster with a gaping mouth as a metaphor for the entrance to the underworld.

Even from a distance, it is quite clear that Chicanna Structure II represents a reptilian monster with a gaping mouth. The large eyes and pointed teeth that overhang the doorway are the easiest detail to spot. Either side of the eyes are the monster’s jade earrings, which look like squared hoops with pendants hanging from them. Curling serpent heads seep from the upper corners of the mouth. More teeth frame the doorway and hang about a metre from the ground (where the mouth spans out to create an upside down “T” shape). Two lower teeth stand up on either side of the entrance on a slightly curved step that represents the tongue. Either side of the doorway is a second set of eyes that belong to a second monster whose gaping mouth extends upwards, using the same teeth and mouth as the monster above the doorway. The popular explanation for this is that this represents the profile view of the same monster that hangs above the doorway. Similar dual-perspectives were a common artistic device in Mayan art, but on Chicanna Structure II we can see significant differences between the front-facing monster and the profile monster. Firstly, the profile monster has a curling “s” shaped nostril (located just below the curling serpent/crocodile of the top jaw). Secondly, the profile monster wears a long, straight nose-flare. Thirdly, a different style of serpent, with long straight body and flopped out tongue, seeps from the corners of the profile monster’s mouth (just beneath the profile monster’s eye). Lastly, the profile monster has a prominent curling brow and curling flames or plant forms emanate from the top of its head. Interestingly, all of these features are found on the stacked long-lipped masks found either side of the doorway (fig. X0674CM).

Hidden Details of the Chicanna Monster

Mayan art was constructed using symbols, ideograms and icons that conveyed a written message in an identical way to their hieroglyphic writing. Mayan art reflected the entangled, disorderly and savage jungle that surrounded them. Complex scenes may appear to be a jumble of squiggles and formless shapes, but to Mayan eyes these complex pictures were packed with purpose and meaning.

One of the more apparent symbols of Chicanna Structure II is the inverted “IK” sign formed by the gaping monster mouth. The “IK” sign was a simple “T” shape that symbolised divine breath/wind. By extending the profile monster’s mouth horizontally either side of the doorway, the artists created an inverted “T” shape (IK sign). An inverted symbol means the opposite of its normal meaning – which in this case would be a lack of breath or life. To the Maya, the doorway of Chicanna Structure II was unmistakably a sign of death and the underworld.

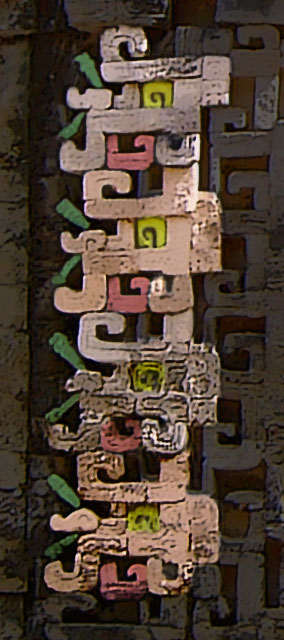

Just beyond the profile monster mouths of Chicanna Structure II, the façade breaks into the looping symbolism of jungle vines. The vines represent the world tree as it sprouts from the underworld to raise the sky and create the middle-world. Flowering from the vines are four long-lipped masks (fig. X0674CM) that represent the four aspects of Chac (known in some regions as Bacab or Pawahtun). X0674CM: Stacked Masks These odd looking characters held up the four corners of the sky once the tree had fully grown. The Chacs were directly related to the sun and named the Red Chac of the East (sunrise), the Black Chac of the West (sunset), the White Chac of the North (hot summer sun), and the Yellow Chac of the South (cool sun of winter). The trunk of the world tree supported the centre of the sky and the Great God, Itzamna, was often pictured in bird-form perched at the top.

X0674CM: Stacked Masks These odd looking characters held up the four corners of the sky once the tree had fully grown. The Chacs were directly related to the sun and named the Red Chac of the East (sunrise), the Black Chac of the West (sunset), the White Chac of the North (hot summer sun), and the Yellow Chac of the South (cool sun of winter). The trunk of the world tree supported the centre of the sky and the Great God, Itzamna, was often pictured in bird-form perched at the top.

The long flares that extend from the noses of the Chac Masks (fig. X0674CM) and the profile monster (fig. X0674) probably represent stingray spines that indicate an association with sacrifice (stingray spines were used to draw blood). Chac, in a singular form, was the God of Rain and blood sacrifices had to be made to Chac in return for his gift of water. That said, it was a character named Stingray Paddler who was renowned for wearing stingray spines. Stingray Paddler and his accomplice Jaguar Paddler, were responsible for laying the first of three hearth stones (known as the Jaguar Throne) to create the foundations for the universe2. Stingray Paddler and Jaguar Paddler represent the daily death and resurrection of the sun, but they are also associated with rain and pictured riding on clouds1. As such, the aged pair may have been considered the ancestors or primordial aspects of Chac. The legendary Chac also played a crucial in the creation myth when he cracked open the earth with thunder and rain to allow the Maize God to be reborn – which is surely an analogy for the agricultural process of sowing kernels of last years’ corn, which then erupted from the ground as fresh plants following the rains. These associations reinforce that the façade of Chicanna Structure II is recounting the creation myth and the origins of agriculture.

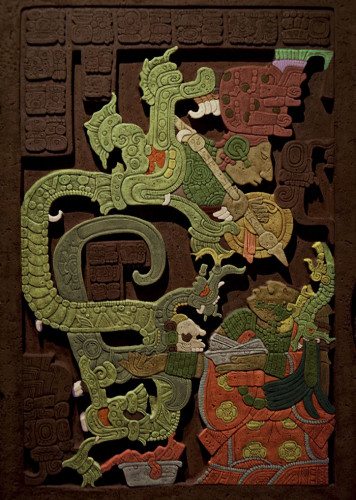

Chac was believed to dwell in caves, where he created water and thunder and his looping lip and brow are symbols of the sacred mountain4. This creates a strong association with the primordial cave entrance to the underworld, but also blurs the image of Chac with another primordial beast known as the Witz’ Monster – whose symbolism also includes curling facial features and whose name, Witz’, was the Maya word for mountain. W0490CC: Witz Monster The Witz’ Monster typically features the Kawak glyph on its forehead (a triangle of 6 circles), which represents drops of water (the beast was formerly called the Cauac Monster on account of this glyph3, but it is now known as the Witz monster on account of the word Witz being found written in its eye). The Witz’ Monster is frequently depicted with divine rulers emerging from its jaws or standing on its head to indicate their divine reincarnation as the Maize God – either posthumously or as part of their accession rites. The Witz monster that is depicted in the Temple of the Foliated Cross at Palenque (fig. W0490CC) exhibits clear similarities with Chicanna Structure II, including a dual or triple perspective design with a front-facing portrait flanked by left and right profile images. Emanating from a cleft in its brow are the precious crops of corn, which then fall around the monster’s head. This cleft is just about visible on the façade of Chicanna Structure II and symbolises the crack in the mountain/earth from which the maize god arose – which is likely to be an analogy for the sun rising on the winter solstice between peaks on the horizon (ancient observers used features on the horizon to record the special days of the year). What is clear from the Palenque example, is that the corn plants curling from the crack create the appearance of a looping brow on the two profile images of the Witz Monster. Therefore, we can be fairly certain that the curled brows on the profile-monsters and Chac Masks of Chicanna Structure II are intended to associate them with maize and agriculture – and quite possibly with the Witz monster itself.

W0490CC: Witz Monster The Witz’ Monster typically features the Kawak glyph on its forehead (a triangle of 6 circles), which represents drops of water (the beast was formerly called the Cauac Monster on account of this glyph3, but it is now known as the Witz monster on account of the word Witz being found written in its eye). The Witz’ Monster is frequently depicted with divine rulers emerging from its jaws or standing on its head to indicate their divine reincarnation as the Maize God – either posthumously or as part of their accession rites. The Witz monster that is depicted in the Temple of the Foliated Cross at Palenque (fig. W0490CC) exhibits clear similarities with Chicanna Structure II, including a dual or triple perspective design with a front-facing portrait flanked by left and right profile images. Emanating from a cleft in its brow are the precious crops of corn, which then fall around the monster’s head. This cleft is just about visible on the façade of Chicanna Structure II and symbolises the crack in the mountain/earth from which the maize god arose – which is likely to be an analogy for the sun rising on the winter solstice between peaks on the horizon (ancient observers used features on the horizon to record the special days of the year). What is clear from the Palenque example, is that the corn plants curling from the crack create the appearance of a looping brow on the two profile images of the Witz Monster. Therefore, we can be fairly certain that the curled brows on the profile-monsters and Chac Masks of Chicanna Structure II are intended to associate them with maize and agriculture – and quite possibly with the Witz monster itself.

Chicanna Structure II Serpent Symbolism

The curling upper-lip and brow of the Chac masks and Witz’ monster are also found on the strange serpents that emerge from the upper jaw of Chicanna Structure II (fig. X0674SNB). It was very common for the monstrous characters of Maya art to feature serpents or a spiralled “fangs” in the corners of their mouths. These symbols appear to have been interchangeable and ever-present, yet their meaning is uncertain.

That said, the distinctive style of the serpents curling from the upper jaw of Chicanna Structure II presents clear parallels with the beasts that flower from the branches of the “world tree” on the Tablet of the Cross and the sarcophagus lid of K’inich Janab Pakal at Palenque (see fig. W0708). The accompanying text names the tree as the Five Square Nosed Beastie Tree and the image shows how the tree supported the four corners of the sky with a beast on each branch and a fifth on the trunk supporting the centre. This imagery draws clear similarities with the four Chacs/Bacab.

Another famous example of this square-nosed beast is found on the Aztec Calendar Stone (fig. W4-0005S), where it appears to represent the perimeter of the earth by tracing the extreme northern and southern transits of the sun on the solstices (from east to west). However, the right-hand serpent may also represent the annual movement of sunrise along the eastern horizon from north (bottom) to south (top), with the left serpent the representing movement of sunset in the west. The Aztec’s called this beast Xiuhcoatl (Fire Serpent) and like Chac he was associated with lightening, war and blood sacrifice. Xiuhcoatl’s jagged tail includes the Aztec trapeze and ray symbol of the solar year5, which dictates a strong link to the fiery annual movement of the sun.

A much older example of the square-nosed beast is found on the frescoed walls of the Tepantitla compound in Teotihuacan (fig W2-0024). There, the square-nosed beastie appears on the headdress of a priest who sows seeds from a pouch. As the priest scatters the seed, incantations rise in speech bubbles filled with symbols of water. The scene demonstrates that at Teotihuacan, a square-nosed beastie was associated with providing rain for the new crops. To invoke its powers, priests would imitate the beast when performing sowing rituals.

These three examples (figs W0708, W4-0005S & W2-0024) represent the beliefs of the most renowned cultures of Mesoamerica (the Maya, Aztec and Teotihuacano). Each culture adopted a square-nosed (long-lipped) reptilian beast and associated with the transit of the sun around the four corners of the sky and included fire, wind and water. Together, these elements were essential to their agricultural method, which involved slashing and burning the previous years’ exhausted crops before the seasonal heavy rains arrived to soak the fertilising ash into the ground. If they began too early, too late, or the wind or rain failed them, then the ash would be blown away or the fires dampened. By recording the weather patterns against the position of the sun, they were able to see that this fiery celestial object was responsible for bringing the conditions on which their agricultural cycle depended. The square-nosed beastie was clearly associated with the sun’s annual circuit around the four corners of the sky: from its rebirth in the south-east on the winter solstice to its peak on the summer solstice in the north-east; from the solstice sunset in the north-west to its death on the eve of winter solstice in the south-west.

Interestingly, the serpents that emerge from lower monster mouth of Chicanna Structure II are very different (fig. X0674S). The square-nosed beastie with its bent back snout is distinctly crocodilian – especially on the Aztec calendar stone, where it features a front leg. The serpents seeping from the lower monster mouths of Chicanna Structure II feature a straight body, short snout and long curling tongue. This straight style of serpent is typically found carved or moulded in stucco on the walls and stairways of sacred buildings. The most iconic examples are found at Chichen Itza (fig. X0473) and Teotihuacan (fig. W2-0031) where they are carved onto balustrades that descend from pyramidal temple structures. These serpents are known to be associated with the sun’s descent from the heavens into the underworld. Evidence of this belief is can still be witnessed at Chichen Itza, where the late afternoon sun on the equinoxes strikes the rounded corners of the “El Castillo” pyramid and casts an undulating snake-like shadow onto the snake-headed balustrades. As the sun descends, the shadow slowly moves and creates the illusion of a snake slithering down the temple’s stairs. The nine steps of the pyramid’s design corresponds with the nine levels of the underworld and complete the story of the sun’s descent into the underworld.

The symbolism of the serpents that emerge from the upper and lower monster mouths of Chicanna Structure II appear to be dualistic, with the upper monster mouth featuring serpents that relate to the yearly motion of the sun, while the lower monster mouth features serpents that relate to the daily passage across the sky and down into the underworld. With this in mind, it is likely that the monster mouth temple is also portraying a duality, with the front facing monster and profile monster(s) being different aspects of a single beastly being, spirit or god. Meanwhile, through the serpent imagery, Chicanna Structure II’s association with the annual cycles of the sun and agriculture becomes almost irrefutable.

X0675L: Structure II Left Doorway

X0675L: Structure II Left Doorway

The Chicanna Structure II Houses

It is easy to focus entirely on the monster mouth façade of Chicanna Structure II and overlook the innocuous doorways that stand either side, but they are very much a part of the building’s function and story. The north chamber features a carved thatched roof, typical of those found on Maya houses (fig. X0675L) and it is likely that the collapsed south doorway was identical. The image and concept of house, known as Na, was prevalent in Maya culture. For the Maya, Na represented ancestry, strength, security, structure, and community. A simple peasant home was Na and the greatest God, Itzam-na, was also Na.

Na features heavily in the Maya Creation Myth, which tells the story of the placing of three-stones by the Gods as they built a hearth in the sky. The hearth was considered the spiritual heart of the house and tying the three hearth stones was the first step to building a new home. Na again features in the name of the place where the first cosmic hearth-stone was set, which was Na-Ho-Chan, or Five-Sky House. This stone, known as the Jaguar Throne, was set by Jaguar Paddler and Stingray Paddler. Knowing, as we do, the Mayans obsession with identifying the recurring cycles of the stars and planets in order to accurately record events and predict the future, it seems logical that Five-Sky-House was an identifiable, observable and measurable place in the sky where Venus or the sun might be seen to reside. As such, Five-Sky-House is a record of time and portents as much as it is a physical place. Similarly, it is likely that the “houses” of Chicanna Structure II were places of observation. In recent years’, it has become increasingly apparent that the Classic Maya designed their structures to be penetrated with beams of light or have windows that aligned with the rising of stars on special calendar days. At Chicanna Structure II, the most obvious mechanism for such hierophanies, would be for the sun to cast light into the three temples as it passed overhead or for the sun to rise directly behind the temple when viewed from a specific location. Unfortunately, the answer to this question was lost along with the collapse of the roof and roof-comb of Chicanna Structure II.

X0675: Triple Entrances of Structure II

X0675: Triple Entrances of Structure II

Chicanna Structure II Architecture & Alignment

Evidence that Chicanna Structure II was built to observe the sun is not only found in the symbolism of its carved façades, but also in its architecture and alignment. Chicanna Structure II features three east facing chambers, built upon a low platform that runs on a north-south axis. This familiar configuration is well studied at Tikal and Uaxactun (100km to the south of Chicanna), where complexes known as E-Groups were built. E-Groups comprise of three structures mounted upon a raised platform on a north-south axis, with a fourth structure built to the west from which the sun could be observed as it rose behind the three structures. The purpose of these complexes was to track three solar events, with the northern structure aligned to the rising sun on the summer solstice, the central structure aligned to either the equinox or zenith and the southern structure aligned with the winter solstice. At Chicanna, the remnants of a large platform located west of Structure II and midway between Structure II and Structure I, may have functioned as viewing platform from which celestial bodies could be observed rising above Chicanna Structure II and setting behind Structure I.

Chicanna Structure II Meaning & Purpose

With its masterful construction and exquisitely carved façade, Chicanna Structure II was certainly designed to broadcast the importance of Chicanna and purpose of the temple. Without knowing anything of ancient Maya beliefs, it is clear that the gaping monster mouth doorway was intended to act as a symbolic entrance to a sinister and beastly realm. This realm was known to the Maya as the underworld and any who walked into the monster’s mouth would have been physically entering the underworld. Once inside, they would be able to communicate with the great ancestors, spirits and gods of the underworld through blood burning rituals. X0714C: Yaxchilan Lintel 25 Knowledge of these rituals comes through carved images that have been discovered. These images show the “Vision Serpent” rising in the form of spiralling smoke from of an offering bowl filled with burning blooded paper (see fig. X0714C). Similar scenes carved on lintels, stelae and tablets, show how blood was let by piercing the tongue or genitals and dripped onto the parchment. These rituals were an integral part of life for Mayan rulers and were designed to honour the gods, ancestors and spirits and earn their favour or receive their prophesies in times of need.

X0714C: Yaxchilan Lintel 25 Knowledge of these rituals comes through carved images that have been discovered. These images show the “Vision Serpent” rising in the form of spiralling smoke from of an offering bowl filled with burning blooded paper (see fig. X0714C). Similar scenes carved on lintels, stelae and tablets, show how blood was let by piercing the tongue or genitals and dripped onto the parchment. These rituals were an integral part of life for Mayan rulers and were designed to honour the gods, ancestors and spirits and earn their favour or receive their prophesies in times of need.

Walking out of the doorway of Chicanna Structure II would have been perceived as rising out of the underworld – an act only possible for the divine and reborn. Therefore, it is possible that rituals also took place within Chicanna Structure II that ended with a newly ordained ruler, recently deceased ruler or newborn prince emerging from the monster’s mouth in a re-enactment of the Maize God’s rebirth from the sacred Witz. Whilst no pictorial evidence of this exists, the consistent image of rulers rising from or appearing in the mouth of the Witz Monster suggests that this type of ritual was very common (the sarcophagus lid of Pakal and the tablets of the Foliated Cross that featured earlier in this article are two of many examples of this).

While the temple and its grotesque monster mouth entrance fundamentally represents the Witz cave, the more eccentric imagery provides clear links to the solar calendar and agriculture. Undoubtedly, the Maya believed the rising of the annual crops were an act of rebirth brought about by the fiery beast we call the sun. This fiery object also lived a cyclical life of birth, death and rebirth. Without any concept of space beyond our earth, the sun must have been considered an immensely powerful living being that moved across the sky like a bird. Each year this fiery beast (the sun) was reborn at sunrise on the winter solstice in the south-east corner of the sky. It then proceeded to grow, bringing new life and precious crops from the ground as it travelled north. Following sunrise on the summer solstice in the north-east corner, it then set in the north-west corner and began to dwindle. As it travelled south, the crops began to die. The cycle of life, death and rebirth began again with the fiery beast setting in the south-west corner of the sky on the eve of the winter solstice.

Most books and articles describe the ornate façade of Chicanna Structure II as a representation of the great god Itzamna. This may be true, but it would be more precise to identify the monster of Chicanna Structure II as an amalgamation of powerful aspects or lesser gods (which arguably is what Itzamna, or “Wizard House”, represents). These lesser gods, or aspects of Itzamna, include characteristics we call Chac, the Witz Monster, the Square-Nosed Beastie and the sky serpent. Together, they were the gods of the agricultural calendar and the people of Chicanna built Structure II as a place where they could give offerings and communicate with these gods to ensure a successful harvest. The alignment and triple-chamber design of Chicanna Structure II allowed to visit them and instruct the people of Chicanna on when to plant, harvest and burn the crops to successfully complete the agricultural cycle. Like a modern church, Chicanna Structure II was a place where the dead could be communicated with, where the great provider could be honoured, where the protection of the community could be secured, where messages from heaven were received, and where answers were found.

References

1:The Cleveland Plaque: Cloudy Places of the Maya Realm – Andrea Stone

2: Handbook to life in the Ancient Maya World – Lynn V. Foster – ISBN-13: 978-0195183634

3: Mesoweb Encycolpaedia: Witz Monster

4: Ceramic Support for the Identity of Classic Maya Architectural Long-Lipped Masks as the Animated Witz

5: British Museum Online Collection: Xiuhcoatl

Great Post, I am happy that I subsribed to your blog 🙂

Are the colors according to remains of colors found at the structures and stelae?

Hi Crischo, Thanks for the comment and for subscribing too! The coloured versions are designed to highlight the different symbols that are otherwise difficult to see. Mayan buildings were generally painted red and the Maya used blue and black paints often too. I have based the colouring on the Post Classic Codices and what things would look like in real life (i.e. sun god = yellow, underworld characters = blue, snakes = green/brown, plants = green, etc.) The aim is simply to help the components of the image stand out for people who aren’t familiar with Mayan art and religion. All the best, Robin

Lovely article, and such an excellent site, I keep coming back.

Thanks Oliver!

What beautiful insights, it does take a trained eye to really grasp the sophistication of these artists and thinkers, thanks for taking the time you are on to something very special.

Thank you M.P.O. I’m currently working on Pakal’s Sarcophagus – which is incredibly sophisticated. The way language and art are bound together both in the Maya hieroglyphic writing and symbolic art allows an incredibly rich amount of detail to be encoded. The more you learn, the more incredible it becomes! Many thanks, Robin