W0767: Plaza AThe archaeological site of Altun Ha was discovered in the 1950s. Only a fraction of Altun Ha has been excavated and relatively little is known about the city, which once covered 25 square miles and had an estimated population of 10,000 people.

W0767: Plaza AThe archaeological site of Altun Ha was discovered in the 1950s. Only a fraction of Altun Ha has been excavated and relatively little is known about the city, which once covered 25 square miles and had an estimated population of 10,000 people.

Excavations have revealed that the earliest settlement was located in an area known as Zone C, which lies just west of Plaza A (beneath the trees behind Structure A1 in fig. W0767). Within Plaza C, two round structures known as C13 and C17 were found to contain post-holes and burials that date from between 900BC and 800BC. Even at this early stage, findings in Zone C suggest that Altun Ha was a place of wealth and religious activity.

The construction of a large reservoir (directly south of the archaeological site) marks the beginning of Altun Ha’s rise from a small Preclassic settlement to Classic Era city. The reservoir’s provenance is unknown, as it has been used continuously through to modern times, but clearly it was constructed to supply water to a large community who were looking to farm extensively. A temple, known as Structure F8, built next to the reservoir in approximately 200AD demonstrates that the city had linked the healthy supply of water with religion and indicates that a structured religious society had begun at Altun Ha. A burial found beneath the structure, which has been dated to 250AD, provides evidence that the funerary rites at Altun Ha matched those found in large Mayan religiopolitical centres. The burial, named Tomb F8/1, includes all the hallmarks of divine Mayan kingship, with grave goods of jade and shell necklaces, jade ear-flares, five pottery vessels, fifty-nine valves of spondylus shell and 245 green obsidian pieces, of which 13 were manufactured into bi-facial blades. Jade was an extremely rare, highly prized and deeply religious commodity, whilst spondylus spines were used in the ritual blood-letting auto-sacrifices that Mayan kings had to perform as part of their divine duties. Therefore, it is safe to say this is the burial of a Mayan lord or high-priest. Curiously, the enormous quantities of obsidian are of a distinctive type known as Pachuca obsidian, which is only found near the distant city of Teotihuacan, in the Mexican Highlands. Tomb F8/1 therefore suggests the involvement of Teotihuacan at Altun Ha at a time that coincides with a period of rapid expansion from settlement to city.

W0761: Structure A1 In the period following the burial in Tomb F8/1 in 250AD, the people of Altun Ha began to construct a new ceremonial centre. Known as Plaza A, the ceremonial space was built adjacent to their existing civic and ceremonial centre in Group C – in fact, Structure A-8 is joined to a series of buildings within Group C and may have been part of the older group before being incorporated in into the new space. Plaza A was classically designed, with a north-south alignment and structures enclosing the plaza on all four sides. This is vastly different to the haphazard buildings of Group C and could be construed as further evidence of an external interest at Altun Ha influencing its construction and design. By 400AD Plaza began to take shape with the building of Structure A3 and the development of Structure A1 into its present shape. Architecturally, Structures A1 and A3 are similar in style to the temples of nearby Lamanai, with protruding tiers creating space for temple enclosures further down the pyramidal base.

W0007: Teotihuacan – Pyramid on the Moon However, it isn’t just Lamanai that employed this technique; the tyrannous pyramids of Teotihuacan could be considered the forerunners of this style. In fact, Temple A1 (fig. W0761) and the Pyramid of the Moon (fig. W0007) have striking similarities, albeit on a vastly reduced scale, which add credence to the theory that Teotihuacan may have influenced the construction of Altun Ha’s new religious centre.

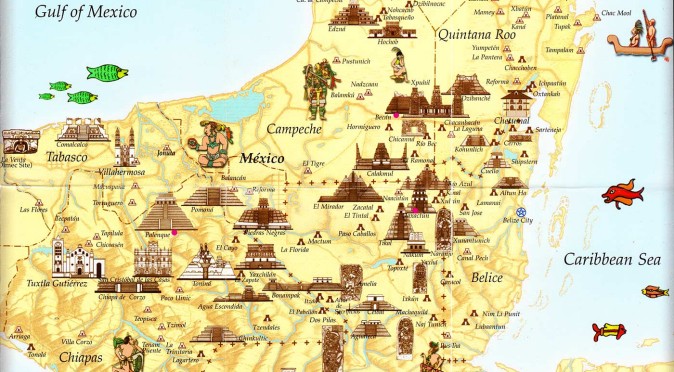

Teotihuacan’s involvement in the region is widely accepted, and it almost certainly held influence over the nearby Mayan city of Tikal in the late 4th century and was instrumental in the founding of Copan and Quirigua in the early 5th century. It would appear that Teotihuacan was extremely interested in jade, which was only found around the Copan area, and wanted to increase its availability along its extensive trade routes, which probably covered the whole of Mesoamerica. Excavations at Altun Ha have revealed a long history of offering jade pieces within its burials, with probably the best example being the 6th century tomb found within Structure A1 of a male interred with over 300 pieces of jade. This huge cache of jade could only have come from the south and is surely evidence that Teotihuacan had managed to increase production through founding Copan, and that jade was being moved by sea to Altun Ha in high quantity.

W0766: Structure B4Around the same time that the cache of jade was being entombed within Structure A1, work was beginning on Structure B4, Altun Ha’s most prominent building (fig. W0766). Structure B4 is the dominating structure of Plaza B and was probably a late addition to a principally residential zone. Plaza B is also aligned, from east to west, with the western and southern sides featuring palatial structures with the exception of B6, which is a small temple. Structure B4 also incorporated a low terrace for a temple enclosure, which again could be associated with nearby Lamanai (in particular Structure N10-43). Although it is very similar to N10-43 at Lamanai, the elongated temple on Structure B-4 featured nine doors (the ruined doorways are still visible – see fig. W0766). This style of temple was very popular at Tikal, where nine sets of “Twin Pyramids” have been uncovered, each of which are built around a small plaza with a nine-doored temple, identical to that built on Structure B4, on the southern flank. However, a far more striking reference to Tikal can be found on Structure B4 in the form of giant carved masks (fig. W0765).

W0765: Mask on Structure B4The masks on Structure B4 have been associated variously with the Sun God and the “Jester God”. The association with the Sun God comes from their likeness to a huge jade head that was found buried within Structure B4 and was thought to resemble the Sun God. The “Jester God”, on the other hand, appears to be the God of Kingship in the eastern Maya region and takes its name from the pointy jester-like hat it is normally pictured wearing (see Lamanai Stela 9). This hat appears to feature on the masks of Structure B4.

W0846: Mask from 5D-33 at Tikal

However, the closest likeness to the masks of Structure B4 are found on Structure 5D-33 at Tikal (fig. W0846). The masks of Structure B-4 at Altun Ha and 5D-33 at Tikal are virtually identical in their appearance and in their carved stone construction. The two buildings also share similar brickwork (as seen in surrounding the masks in figs W0765 & W0846). Structure 5D-33 was erected between 425AD and 450AD, during the period which it is believed that Teotihuacan held sway over Tikal and the exact time that a lord from the Tikal region, K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’, arrived at Copan dressed in the lordly regalia of Teotihuacan to take command of the jade trade at source. The hat on the mask at Tikal is also very similar with a rounded crest on top. It seems likely that the pointedness of the hat on the mask of Structure B4 is the result exposure to the elements, and it would have actually been the same as that of Structure 5D-33, which was preserved under subsequent constructions of the temple.

W0766J: Jade HeadThe prominent nose on the mask at Tikal can also be seen in the mask of Structure B4 – and again it is likely that the mask at Altun Ha was once the same as that of Tikal. This nose is very similar to the beak that the the Jade Head exhibits (see fig W0766J). The mouth shape of the Jade Head, the Tikal mask and the Structure B4 Mask are all very similar too, suggesting that all three are all representative of the same unknown deity. The Jade Head was found buried in a tomb within the 7th phase of Structure B4’s construction, which is thought to date between 600-650AD. However, the only fragmentary remains of a male skeleton were found in the burial, designated Tomb B-4/7, suggesting that the skeleton and the head were relics interred within the temple to add supernatural power – therefore, they could be much older. The Jade Head is the largest single piece of carved jade ever found in Mesoamerica, which alone designates its importance – as well as that of Temple B4, the man who was buried there and of Altun Ha as a whole. Exactly which god the Jade Head or the masks symbolise is unknown, but it was clearly a very important deity to Tikal and the people of Altun Ha. The composition of the head, in jade, brings Altun Ha’s history full circle and confirms its importance in the trade in jade.

The wealth of the people at Altun Ha from its very beginnings as a settlement and the relatively low population it maintained upon becoming a city, both seem to suggest that Altun Ha was making a lot of money doing very little. The fertility of the land around the city was also meagre, suggesting the city was never built around the abundance produced by farming. One prominent suggestion is that Altun Ha was a centre for the manufacture of carved jade, and this ability is certainly evidenced by the Jade Head. This theory would also explain the incredible volumes jade fragments that were buried with their elite, as these could have been the chippings left over from their carvings. The people of Altun Ha also, somewhat unusually, burned jade and copal during rituals around the masonry altars of Structure B4, which further emphasises that jade was not a rare commodity, although it was still considered deeply religious. A Late Classic vase found in Tomb 2 at Copan, which dates to 700AD, has been chemically proven to have come from the workshops of Altun Ha, which confirms that trade between the jade mining region of Copan was taking place, and that Altun Ha was a centre for the production of artistic artefacts.

In summary, the evidence suggests that Altun Ha rose to prominence as a centre for the production of carved jade and traded with the super-power Teotihuacan very early on. Then, with the assistance of Teotihuacan’s trading might, or possibly following them taking control, the city of Altun Ha was planned and built. Later, Tikal became Teotihuacan’s regional centre of commerce and the relationship between the three cities grew. Later still, the Teotihuacan-Tikal alliance founded Copan and moved huge quantities of jade around to Altun Ha to be carved, which lead to the city’s rapid growth and development in the 5th and 6th centuries, and its continued wealth and success into the 9th century when Tikal collapsed. As stated at the beginning of this article, much is still to be uncovered at Altun Ha and a lot has yet to be learned, but this does seem to be the core of Altun Ha’s history.